June 8, 2018

CBC Junior Investigator, Sadie Wignall, NU — a cell biologist featured by the American Society for Cell Biology

Congratulations to Sadie Wignall, NU, who is featured in the American Society for Cell Biology (ASCB) Careers, 2018 edition, entitled “How Cell Biologists Work.” Sadie is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Molecular Biosciences at NU and studies meiotic cell divisions in oocytes. Sadie is also a CBC Junior Investigator — she was hired by NU in 2011 with help of a generous CBC Recruitment Resources Award, issued to outstanding young candidates with demonstrated records of excellence who, at the time, were entering their first faculty positions as tenure-track assistant professors. In addition, Sadie was later a recipient of a CBC Catalyst Award, which she received in 2016 for a project: “Spatial and Temporal Dissection of Mouse Meiotic Chromosome Segregation.” Sadie has since served on the CBC Catalyst Review Board (2017). CBC is grateful for Sadie’s service and wishes her continuous successes in her scientific endeavors.

How Cell Biologists Work with Sadie Wignall of Northwestern University

The American Society for Cell Biology (ASCB), Careers | by Kira L. Glynn | May 25, 2018

I am excited to join the team for the 2018 edition of “How Cell Biologists Work.” Jenny Heppert started this series as a graduate student when she became curious about how different cell biologists approach science and life as career researchers. I am currently a graduate student in Bob Goldstein’s lab at UNC-Chapel Hill, studying primordial germ cell specification in the emerging model organism, Hypsibius exemplaris (aka “water bears”). In conducting and sharing these interviews, Jenny and I hope that other trainees and cell biologists can glean useful (or at least interesting!) insights into ‘how cell biologists work. I am especially eager to uncover how scientists find balance both professionally and personally since, after all, we are humans and not data-generating robots.

Sadie Wignall. Photo by Danna Freedman

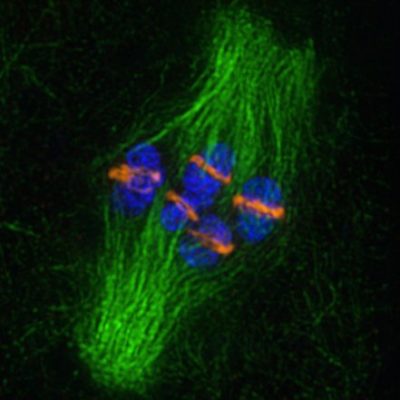

Our featured cell biologist this month is Sadie Wignall, PhD, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Molecular Biosciences at Northwestern University in Evanston, IL (near Chicago). The Wignall lab studies meiotic cell divisions in oocytes, which (in most metazoans) amazingly segregate their chromosomes without centrosomes. The lab utilizes the optically transparent and genetically tractable Caenorhabditis elegans oocyte as a model to uncover how a cell can divide in the absence of microtubule organizing centrosomes. They endogenously label multiple components of centrosome-free spindles using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing and utilize high-resolution microscopy to image these proteins in C. elegans oocytes as they develop inside adult gonads. The Wignall lab recently discovered centriole-independent mechanisms of microtubule bundling and spindle organization (Mullen and Wignall. PLOS Genetics, 2017). Recent work in the lab has also revealed a spindle assembly checkpoint-independent mechanism for detecting errors during oocyte meiosis, in the absence of end-on kinetochore attachments (Davis-Roca et al. Journal of Cell Biology, 2017). In addition to providing pivotal research about spindle assembly during oocyte meiosis, both of these findings more broadly inform the cell division community of centrosome-independent mechanisms of spindle assembly, which are more difficult to discover in mitotically dividing cells that inherently rely on centrosomes. Wignall has received many accolades thus far in her career, including the Damon Runyon-Rachleff Innovation Award, a March of Dimes Basil O’Conner Starter Scholar Award, and a V Foundation for Cancer Research “V Scholar” Award, as well as a Distinguished Teaching Award from Northwestern University for her ingenuity in undergraduate cell biology education.

Super-resolution image of a spindle formed in a C. elegans oocyte lacking centrosomes. Shown are microtubules (green), chromosomes (blue), and a protein complex essential for chromosome segregation that forms a ring around the center of each chromosome (red). Work in the Wignall lab focuses on how these acentrosomal spindles form and facilitate chromosome movements. Image by Keila Torre-Santiago.

Let’s start with your name: Sadie Wignall @swignall

Location: Evanston, IL

Position: Assistant Professor

Current Mobile Device(s): iPhone 8

Current Computer(s): MacBook Pro

Lab Website: http://sites.northwestern.edu/wignall-lab/

What kind of research do you do?

My lab studies how spindles form and how chromosomes segregate during cell division, focusing on the specialized divisions of female reproductive cells (oocytes). These divisions are important to understand because they are crucial for sexual reproduction, and they are also fascinating because they use unique mechanisms. Unlike most dividing cells, oocytes of most species lack centrosomes, so spindles must assemble in their absence. Our research is generating insights into how these acentrosomal spindles form and mediate chromosome segregation.

What is one word that best describes how you work:

Variably. One challenge of being a faculty member is that the job is constantly changing, depending on the balance between various responsibilities at any given moment (whether teaching, mentoring, grant/paper writing, traveling, etc.). I find I am always adapting my work style to meet the particular challenges of the moment.

What excites you most about your current work?

I started my lab at Northwestern seven years ago, and so I am just now at the point where students who joined in the first few years have either recently graduated or are nearing graduation. When starting a new lab, so much time is spent seeding projects that you hope will work. It is exciting to see those projects now getting published and to think about all of the unexpected discoveries along the way that have taken our research in new directions. We now have ongoing projects in the lab that I could never have anticipated in year one!

Can you describe one experience from your life or training that set you on this path?

In high school, I had an awesome AP Biology class, taught by a dynamic and inspiring teacher. I was also able to get involved in research through a high school summer internship, where I got to work with this teacher and a group of other students, tromping through forests and measuring tree growth as part of an ecology project. This experience inspired me to enter college as a biology major and to seek out research experiences as an undergrad.

Years later, my desire to run a lab was strongly influenced by my graduate advisor, Rebecca Heald. I was one of her first graduate students, so I was able to see what it was like to set up a lab. She was a great scientific mentor and she also made a big effort to establish a positive lab culture. Many of my own lab traditions (champagne celebrations for paper submissions, margarita parties, etc.) are inspired by my days in her lab.

What is one part of your current position or project that you find challenging?

Obtaining funding! The funding climate (in the USA) has been tough in recent years, and it is common for faculty to go through multiple rounds of applications before something finally comes through. I do have NIH funding currently, but it took multiple tries–perseverance is essential in this job.

Do you have any specific advice about establishing or running a lab for new or aspiring faculty?

When I started my lab, many people told me that I should actively seek out senior colleagues to serve as mentors. This was terrific advice, and I have had great mentors both inside and outside my institution. However, one thing that I have since come to appreciate is the importance of also creating a network of peers at similar career stages. At Northwestern, I have great junior faculty friends both inside and outside my department. In addition, I have made some wonderful friends over the years at conferences–people who I met when I was a graduate student or postdoc who I look forward to seeing every year at summer meetings and at the ASCB/EMBO meeting. While it goes without saying that having friends is a good thing, I didn’t realize until recently how much this network of colleagues would help me career-wise. These friends have invited me to give talks at their institutions, have been sounding boards for scientific ideas, have provided grant writing and lab management advice, and have served as cheerleaders to get me through setbacks such as grant rejections. I am lucky to have them!

What (if any) are your preferred methods for training your students to become independent scientists?

I try to create an environment where trainees have the freedom to come up with their own ideas and to provide their peers with suggestions and advice–I think it’s fantastic that not every idea originates with me! One thing that works well is that we have small “subgroups” in the lab, each composed of three to four lab members working on related topics. Each subgroup has a roundtable discussion every two weeks where every person in the group gives an update on their project. These meetings not only help me keep up to date on everyone’s progress and provide me with a regular way to provide feedback, but they also create a team mentality within the lab, where trainees advise and support each other. I think this helps them develop as scientists and as future mentors.

What’s your best time-saving shortcut/lifehack?

Amazon Prime and Amazon Subscribe and Save! It saves so much time that I would otherwise spend shopping for household items and other necessities.

What’s your favorite to-do list manager (digital or analog)?

Google calendar. I have three separate calendars: one for my own work schedule, one shared with lab members for Wignall lab events, and another shared with my husband for family scheduling. I love that I can display them all together in the same place. If something doesn’t make it onto one of those calendars I am likely to forget about it!

What apps/software/language/tools can’t you live without?

I use Google Docs a lot–creating shared documents with my trainees to catalog/organize experimental ideas or to collaboratively draft outlines of manuscripts. Also, since we do a lot of imaging in the lab, I rely heavily on Photoshop.

Besides your phone and computer, what gadget can’t you live without? And how do you use it?

iPad. I use it for entertainment (as an eReader and for watching shows on the Netflix app) and I also take it to conferences to view meeting programs–I especially like using it to access the ASCB meeting app! iPads also come in handy when traveling with kids–great for keeping them entertained in airports or on plane rides.

A network of peer colleagues is invaluable! From left to right are Soni Lacefield (Associate Professor, University of Indiana), Sadie Wignall, Diana Libuda (Assistant Professor, University of Oregon), Francesca Cole (Assistant Professor, MD Anderson Cancer Center), and Needhi Bhalla (Associate Professor, UC Santa Cruz), at the EMBO Conference on Meiosis, August 2017.

When/ where do you find the most creative inspiration for your research?

This is not the most creative answer, but I get many of my best ideas when I attend scientific meetings. Our work focuses on the specialized divisions of female reproductive cells, which use different mechanisms from mitotically dividing cells, but we find that often some of the same principles are employed. There have been countless times that I have gotten ideas for experiments from hearing about new discoveries in the mitosis field. I jot down ideas at the end of my meeting notebooks and discuss them with my students when I return to lab.

What is one thing you never fail to do (in or outside of lab), no matter how busy you are?

Spend time with my husband and kids.

Who is one of your scientific heroes, and what is one quality you admire in that person?

Ted Salmon. I went to college at UNC-Chapel Hill, and I did undergraduate research in his lab. I don’t think I would be a scientist today if it wasn’t for him! Ted has a genuine love for fundamental discovery-driven science, and his enthusiasm has spread to many generations of Salmon lab alumni. He is also a genuinely nice human being who always values collaboration over competition–this has strongly influenced my own attitudes about science.

What do you like to read, learn, or think about outside of lab?

I regularly listen to a variety of podcasts–from NPR-produced ones such as “This American Life, “Planet Money,” and “Serial,” to political podcasts like “Pod Save America” (shout-out to other “friends of the pod”!).

Are there any causes or initiatives in or outside of science that you are particularly passionate about?

I think it is incredibly important to advocate for fundamental, discovery-driven science. Last year I attended the March for Science in Chicago with members of my lab and with my family, and it was great to see so many people out there supporting scientists and the scientific enterprise. Just this month (May 2018), I attended ASCB’s Capitol Hill Day, where I got to meet with members of Congress and congressional staffers to advocate for increased NIH/NSF funding. This was my first time participating in this event, and I found it to be a really rewarding experience.

What’s your sleep routine like?

I wake up every day between 6:00 and 6:30 am (whenever my kids start making noise), so to get enough sleep I try to go to bed by 11:00 pm. This is not always possible, for example, if I’m pushing towards a big deadline, but I do my best to keep a regular sleep schedule.

What’s the best advice you’ve received or some advice you’d like to share with trainees?

Early in my postdoc, before I began to contemplate having kids myself, I ended up in a casual conversation at a conference with Terry Orr-Weaver. The issue of parenthood came up, and she mentioned that people often get overwhelmed when they first have kids because they have trouble juggling parental and work responsibilities, unfortunately leading some to drop out of science. However, she noted that although the first few years of parenthood can be challenging, if you are able to just push through that period, then you come out the other side with an awesome career that has flexible hours compatible with family life. Years later, I started my own faculty job at Northwestern with a seven-week-old baby (and then subsequently had a second child two and a half years later), and I can’t tell you the number of times that I thought of those words! While things were very tough at first, mostly due to sleep deprivation and the constant demands of infants and toddlers, life is now so much easier just a few years later. I am incredibly grateful that she shared her perspective, as it helped me push through those years–I’m now on the other side with a career that I love.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are the views of the author(s) and do not represent the official policy or position of ASCB.

Source:

Adapted (with modifications) from the The American Society for Cell Biology (ASCB), Careers , by Kira L. Glynn, published on May 25, 2018.

See also:

Sadie Wignall, NU, has following ties to CBC:

- CBC Catalyst Review Board (2016-2017):

▸ CBC Catalyst Review Board; Current Membership

Sadie Wignall, NU — Board Member - CBC Catalyst Award (2016):

▸ Spatial and Temporal Dissection of Mouse Meiotic Chromosome Segregation

PIs: Sadie Wignall, and Michael Glotzer, UChicago - CBC Recruitment Resources Award (2011):

▸ Four New Faculty Receive CBC Junior Investigator Awards

Sadie Wignall, NU — CBC Junior Investigator